Most mornings, Jayson Peña wakes up early and loads the back of his Chevy Suburban with pigeons.

Using his bare hands, he pulls the birds out of a white-shingled loft in the backyard of his home in Avon, Connecticut. He grabs each grey body around its midsection, his thick brown fingers wrapping easily around the bird’s stomach and tail, holding its feet in place. The air around the coop is warm and acrid with guano—pigeon droppings—but the musk isn’t quite so bad in the morning. The birds get settled in their boxes, fleshy pink feet poking in and out, feather tips flaring upwards as they adjust their wings, getting caught momentarily between the bars. Dozens of pairs of red eyes blink up at Peña as he closes the crate door. One on top of the other, the boxes go into the trunk.

Then comes a rustle, a thrash, and a communal unfurling:

a battery of wings, bodies, and twig-thin legs bursts forth.

Peña backs down the driveway and drives through his neighborhood before merging onto Highway 4. Today, he pulls off of the road at the Bed Bath & Beyond in Farmington, though he could just as easily stop at the cemetery off of Huckleberry Hill Road, or the grassy patch along the wide curve of Highway 177, or in the parking lot of a strip mall.

With his car engine stopped, Peña pops the trunk. He loosens the metal clasps of the bottom crate first, letting the leather flap door fall open, and for a moment, there is no movement at all.

And then comes a rustle, a thrash, and a communal unfurling: a battery of wings, bodies, and twig-thin legs bursts forth. When that crate is empty, Peña loosens the ties on the second, and the process repeats.

A flock of mottled grey creatures takes to the sky, circles the lot, and is gone.

Peña is in no rush. Today is a training day for the young birds, and since they’re only flying ten miles—a fraction of the length of their next race—there’s no way he can beat them back home. These are thoroughbred racing pigeons, after all: on a clear day, they can clock in an average speed of around 90 miles per hour.

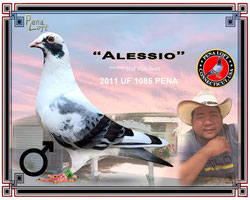

Peña is a member of the Connecticut Classic Pigeon Racing Club, a loose confederation of middle-aged men living in Avon, Hartford, New Haven, and other small Connecticut hamlets who share a love of birds and a passion for breeding them. Each man’s goal is to create, after many generations of pigeons, a bloodline whose birds are faster and stronger and smarter than the birds that came before them. They want to create champions.

But only so much can be predicted by a bird’s genealogy. Weather patterns, predatory hawks, power lines, fatigue, confusion, and other factors all alter a bird’s ability to return home.

And, all else equal, much of a bird’s success relies on its training.

Pigeon races, unlike similar competitions for grounded species, have no set path. Birds from multiple lofts across a region are brought to one starting point, usually a hundred or more

miles from the pigeons’ homes, and released. From there, each bird charts his own way back.

Ornithologists estimate there are about 400 million pigeons worldwide, of which more than 60 million—or about 15 percent—are domesticated racing pigeons. And rearing these 60 million are somewhere around 1.2 million breeders (or, as Peña and his cohort prefer to be called, “pigeon fanciers”). Once they are released, the pigeons’ keeper simply waits for their return. The rest is up to the birds.

—

Birds have fascinated Peña since his childhood. He grew up in the rural Quezon province of the Philippines during a period of martial law that began in 1972. His town was overrun with semi-domesticated free-range chickens. “Shake a can, and two or three hundred would come running out of the bushes expecting food from you,” Peña says. At night, the chickens roosted in the trees to avoid ground predators. The guttural, clucking murmur in the dark Quezon night became the white noise of Peña’s childhood. When he was seven, he asked his family for his own birds. Their neighbors had a loft of pigeons, he mentioned to his father. Couldn’t they get some, too? Peña’s parents spoke with the neighbors, who were more than happy to share two brooding pigeons from their overpopulated coop.

But four years later, Peña’s family moved to an apartment in the crowded capital city of Manila—no more chicken trees, no more Quezon fields, and no more room for a pigeon loft.

Shortly after high school, he moved again to Guam for the island’s “party lifestyle,” where he saw the newspaper advertisement that would reroute his life entirely: Athena Healthcare, a Farmington, Connecticut-based elder care company, was looking for applicants to fill positions as Certified Nursing Assistants.

“Why not?” Peña remembers thinking to himself as he held the Sunday paper. He had never been to the mainland. Within a week, Peña told his friends he was leaving the island. No one believed him, but the next morning—carrying only his backpack, which held one change of clothes and his passport—Peña boarded a Greyhound bus that took him, along with dozens of other Filipino and Guamanian passengers, to the Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport in Guam.

—

“But what is it that makes a racing pigeon such an object of interest to such vast sections of the population in so many parts of the world?” ponders Anthony F. Sciabarassi in the January

2015 issue of Pigeon Racing Digest. “It is my sincere belief that the answer lies very largely in the character of the bird itself. First and foremost is the bird’s own love of

home.”

Kenneth Kuester, a materials assistant with Yale University’s Ecology department and a pigeon fancier himself, tells me that this homeward drive is one of the most baffling aspects of the

pigeon. He’s been racing birds out of his home in East Haven since the 1970s, and says that even after almost fifty years of breeding, raising, and training them, he hasn’t figured out

what it is that makes them so intent on getting home. Their desire to get back to their roost is so strong, Kuester says, that the birds will literally lose limbs, break bones, and still

return to the coop.

“Each year, I lose about 25 percent of my young birds, mostly to Cooper’s hawks and power lines,” he says. “Sometimes they’ll return and you can see that their keel,” he motions towards his sternum, “right here, is just split in half from hitting a utility wire.” In those cases, Kuester says, the bird usually dies not long after his return. But unless the power line kills him on impact, or unless the hawk snatches him in mid-air, the bird will usually keep going, full-speed, until, exhausted, he finds his home.

Peña attests to this seemingly supernatural drive towards home, recalling that some of his pigeons have returned to the coop more than two years after leaving for a race (he identifies each bird using an ID band on their leg). Each time this happens, he is surprised: “You still remember me after two years not in my coop?” Usually, pigeon fanciers assume that the birds’ homeward pull comes from a sort of imprinting process—like a baby duck who assumes the first animal he sees is his mother. But Peña said that in one case, a bird he purchased as an adult found its way to the loft after an entire year away. Sometimes, even late in life, the birds choose a new home.

—

Peña didn’t intend to stay in Connecticut. When he arrived in 2000, Athena Healthcare moved him, along with the other new immigrants in his program, into an eight-bedroom home in

Torrington. Peña’s English was poor, which made the job and the transition challenging, but for the first six months of his stay in America, Athena provided rent, a transport van, and

$300 per week in wages. After the six months were up, Peña was told to find a place of his own.

Despite the abrupt eviction from the home, and the difficulty of saving up enough money to acquire a car and an apartment on only $300 a week, Peña felt exhilarated by the opportunities

he saw in Connecticut. He applied for his green card to stay.

Not long after arriving, Peña met Kristina Guanzon—a nurse from the Philippines who had arrived in the United States a few years before, and who had made her way to Connecticut via

Chicago. Like Peña, she had a round face, olive skin, black hair, and an easy smile. They fell in love.

“I traveled halfway around the world to meet you,” he remembers telling her.

In 2004, they returned to Peña’s home in the Philippines, on the island of Zebu, so that Peña could ask her parents for her hand in marriage. As is customary in Filipino tradition, they were married near her childhood home. At the ceremony, Kristina and Peña released two white pigeons.

“You always hope they’re in good hands, that someone’s taking care of them. That they’re not dead. But that’s the law of the land. It’s their freedom.”

A week later, they returned to Connecticut, and Peña decided to buy his first pigeon in North America. “I think I found it on Craigslist,” Peña recalls. He drove to Massachusetts to pick up the bird and quickly began forging a network of fellow racers, first on Craigslist and eventually on Facebook. Since then, Peña’s friendships with other pigeon fanciers have developed to the point that he calls them a second family. “Quality friends. It’s hard to find those friends,” he says. “They’ll take their shirt off their back for you.”

Despite finding a support system in the racing community, Peña claims that his hobby did not ease his process of moving to the United States. “It was actually hard in the beginning,” he says. He needed to find a home of his own in Connecticut, and he sought a town that would permit residents to keep pigeon coops.

Fortunately, Peña’s wife, Guanzon, has always been supportive of his passion for pigeons, given the positive influence that pigeon racing has on his lifestyle. Instead of frequenting bars or causing trouble, as Peña claims he otherwise might, he devotes nearly all of his spare time outside the home to pigeons. “She knows where to find me,” Peña says of his wife, pausing to laugh as he reflects upon his time management. “I’ll be in my pigeon coop or I’ll be at my buddy’s where he’s got his pigeons.”

—

On race days, Peña waits outside of the loft in his backyard, throwing darts. Somewhere off in upstate New York, or rural Ohio, or Massachusetts, or Vermont, or New Hampshire, or Pennsylvania, a truck full of pigeons—some of them belonging to Peña—pulls into a wide, green clearing.

With a heaving sound, the sliding metal doors of the truck click up and up until the shelves of birds are exposed. A switch is flipped, the doors slide open, and a battery of birds spills

out. Bodies tumble one into the next, wings thwacking onto wings, until, with a lifting motion, the birds spiral upwards, survey the land, and disperse, each making his or her own way

home.

“When you let them out of the coop, they’re free,” Peña says as he watches his older retired birds waddle around on the roof of his house. “They’re pretty much on their own. If you love

the pigeons, you watch for them to return. If they don’t like you, they just won’t come back to your house.” It has started to rain a little bit. “You always hope they’re in good hands,

that someone’s taking care of them. That they’re not dead. But that’s the law of the land. It’s their freedom.”